Pubblicato da Shazarch il 18 Mar 2021

Septizodium

203 AD, Rome

Manufatto archeologico

Entering Rome from the south along the ancient Appian Way in 203 AD, visitors were greeted with a spectacular surprise. A stunning monumental facade, commissioned by Emperor Septimius Severus, awaited them. This grand structure was deliberately designed to awe everyone arriving in the city from the south, specifically from Severus's homeland, Africa.

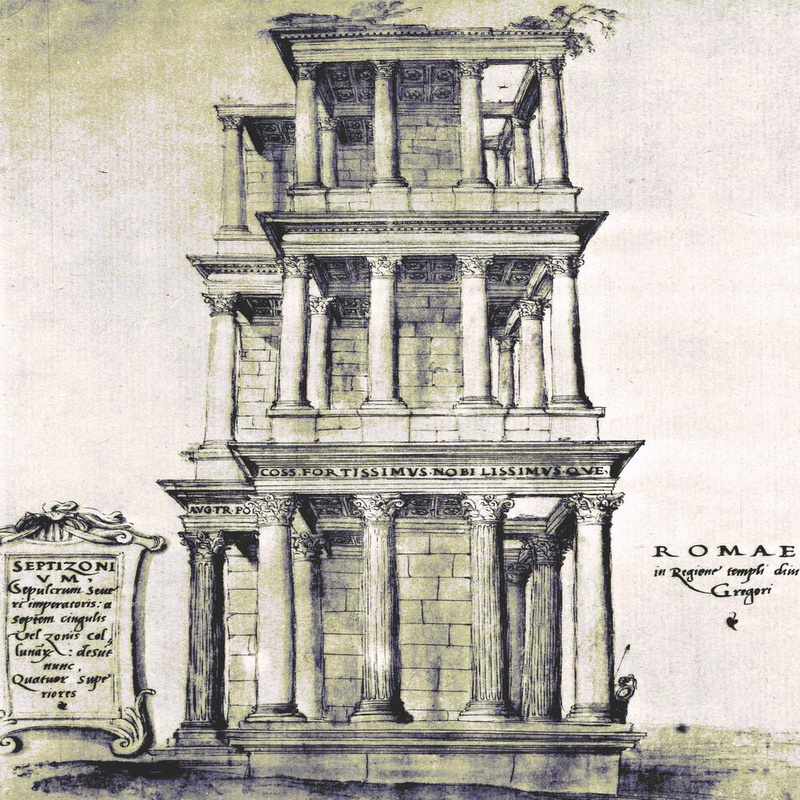

In reality, this was a new entrance added to the already impressive Domus Augustana of Domitian, located in the southeast corner of the Palatine Hill. The facade was a theatrical backdrop, originally reaching 30 meters in height and extending over 90 meters in width. It was completely adorned with columns made of colored marbles, featuring composite capitals across three orders and statues.

The statues likely represented either the personifications of the seven planets or the seven days of the week. This aligns with the astral significance of the building, as suggested by its name "Septizodium," and supported by the emperor's fascination with astrology. Severus was so interested in horoscopes and astrological predictions that, after becoming a widower to Paccia Marciana, he relied on the stars to marry the Syrian Julia Domna, whose horoscope predicted her marriage to a king.

At the center of the main apse was a statue of the emperor, dedicated by the urban prefect L. Fabius Cilo, later accompanied by a statue of a river deity.

Architecturally, the Septizodium was essentially a "facade" type nymphaeum, mimicking a theater scene. At its base, a long basin lined with Luna marble collected water.

After the abandonment of the Palatine Hill as the central seat of imperial power, the building fell into ruin. The central section collapsed due to neglect and earthquakes, and systematic material removal occurred over the centuries, as was common in the Middle Ages.

Although partially preserved until the 16th century, the building was ultimately demolished by order of Pope Sixtus V, who repurposed its valuable materials for new monuments.

Today, all that remains of it are its plan shown in the Forma Urbis Severiana, some Renaissance drawings, and some structural remains unearthed in recent excavations, along with fragments of decorative sculptures (now housed in the Antiquarium on the Palatine), revealing a glimpse into its past grandeur.